Jimmy Wright: Twenty Years of Paintings and Pastels

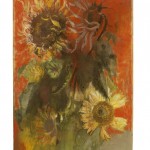

Wright has spent nearly two decades working with the image of the sunflower, primarily in pastel but also in oil. The challenge to constantly reinvent this singular image has defined his career. Working within a tradition of painting that contains iconic works by such seminal artists as VincentVan Gogh, Odilon Redon and Henri Matisse, Wright has managed to forge his own singular style, proving that innovation is possible amidst the precedents of art history.The sunflower has become endlessly inspirational because he says, “They’re images from within, rendered with skills learned from observation.”

Wright stumbled upon the subject matter in 1988 when he became the caretaker of a friend who was seriously ill. Overwhelmed by the physical and mental energies needed for this task, Wright was looking for a way to maintain his own sense of self as he spent most of his time caring for his friend. He needed a method of painting that would allow him to work intermittently, and still life became the perfect outlet for that. After buying some sunflowers at the market, Wright forgot about them and, by the time he noticed them again,the petals had withered. This intrigued him and prompted him to paint them; he was pleased with the results and thus began his fascination with the sunflower. Wright says, “It represented a new way for me to approach painting through observation rather than through fantasy and formal strategies. It [the sunflower] is always there in the studio waiting to be observed and painted.” His first sunflower paintings were in oil, but when he realized their potential, he began to visualize a series in pastel, even though he had never worked in the medium. He soon found that pastel was nearly perfect for his particular stylistic approach.

Based on the model of 18th century botanical prints, Wright’s first sunflowers were isolated, floating on a sea of white but, instead of a scientifically accurate rendering, he went for the expressive and the figurative. Over time, he has evolved the form into all-over compositions with blazing colors, often unnaturally bright, set against pulsing, crackling backgrounds. Each sunflower is imbued with almost humanistic qualities as the petals and stems bend and contort, like flailing appendages, in expressive emotion. More recently he has added chrysanthemums, gladiolas, butterflies and moths – often filling the work with intertwining flowers. Wright works from life, with both dried and fresh flowers arranged in the studio. However, he uses the flowers more as an inspiration, pausing to handle them again and again, taking time to look at them as the images unfold before him. His studio is also filled with a variety of stimuli from sketches to photographs and postcards which find their way into each work in the form of color or composition. Wright notes that “The more abstract the composition or un-naturalistic and expressive the color, observations from life makes the subject more convincing.”

Part of what enables Wright to continually reinvent his subject matter is that he approaches each new work as if it were his first. “Now, years later,” he says, “part of the challenge that I enjoy is finding a fresh approach to the same subject.” It is a testament to his creativity and superb skills that he has not repeated himself and continues to bring a vitality and freshness to each work. Wright admits that you must have a solid foundation in the fundamentals of art before you can begin to work expressively. His draftsman skills are superb, gleaned from a strong academic training in drawing during his first years at Murray State College in Kentucky. He gained crucial insight into color theory in classes taken at the Art Institute of Chicago where he earned a B.F.A. with honors. As a student Wright also experimented with printmaking, primarily etching and serigraphy which he says was “a big influence on how I work. I love the process and how there are certain steps that must be followed. But then you can rework the image and make adjustments.”

Although the image of the sunflower has been a dominant theme in his work, Wright found that it was still important to find a reprieve from the subject matter and he began making self-portraits in order to “regroup and to step back from one subject and look at something else.” Wright began a series of six pastel self-portraits in 2002, just after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. He began the first self-portrait with a very straightforward depiction of the face, drawn onto a very soft, French handmade paper, Matier, that has the feel of blotting paper. Wright worked with soft pastels to minimize the abrasion of the surface and chose colors that were complimentary to the grey of the paper. As he continued the series, he utilized the vulnerability of the paper to emphasize the raw emotions brought forth by the acts of 9/11. According to Wright, “The floating head is a motif inspired by Redon. I perched the head on the lower edge of the paper to emphasize the physicality of its precarious balance and as a metaphor for the power of emotion to unbalance rational thought. These aren’t literal self-portraits. Each individual portrait in the series depicts a fleeting surge of emotion as it rolls across consciousness.”

Using the delicacy of the paper itself as an integral component to convey the emotions of the piece is both unique and typical of Wright’s technique; he doesn’t simply draw or paint an object but he uncovers the object and the form by exploring all aspects of the piece – from the softness of the pastel to the weight and absorbency of the paper itself. In many ways, each piece is an exercise in the formal attributes of art – color, texture, and line; it is through exploring the varieties of these tools that each sunflower or portrait develops.

Wright approaches both oil and pastel with a similar technique. He builds layer upon layer beginning with the background and working towards the foreground, constantly reworking and revising until the form, composition and palette reveal themselves. He is “looking for something that has not been visualized and part of my job as an artist is to recognize that when it is there.” Wright nurtures the elements of chance and unpredictability noting that each painting is a spontaneous act. He is a lethal editor, slashing and over-painting any part of the piece that does not work as a whole, regardless of the quality of the individual piece. Wright says that “the most important time in a painting is the last four hours that I am working on it. In an attempt to find the right balance of all the elements, I may take a large palette knife and radically move paint about the canvas, removing large areas and layering over other areas.”

With his more recent Floating Sunflower series Wright has been exploring abstract formal space. He interprets realism through modernism and this series is an obvious extension of that approach; as he works he is always aware that there is an abstract or flat surface beneath the expressionistic rendering of the form. Wright “wanted a painting that required, on the part of the viewer, contemplative looking. The color and the space have no reference to realism. I am primarily interested in how an inanimate substance such as oil paint can in certain situations become the repository and signifier of human emotions. I enjoy seeing the shock of recognition when someone first experiences bringing all the abstract elements together in my work for both an emotional and intellectual experience.” Wright notes that “Substances like oil paint and pastel – those are my words,” which he uses to convey emotions. He admits that what he does is not radical, “but intense because emotions are intense.”

In the last twenty years, Jimmy Wright has proven that there is room for innovation and personal expression in the most traditional of genres. Basing each work in the solid and fundamental tools of the artist – superb draftsmanship and an intuitive understanding of color, line and texture, Wright breathes life and emotion into his sunflowers and self-portraits through chance, spontaneity and the fostering of unpredictability.

Sarah E. Buhr

Curator of Exhibitions

Springfield Art Museum